But they always seem to be in the news! I have gotten curious about them because it seems like every time some kind of construction project is stopped, it is because an "endangered Salamander" is behind the stoppage.

Cases in point:

- The Cow Knob Salamander, an endangered species, caused the Forest Service to deny a permit sought to locate a natural gas pipeline near Ramsey's Draft Wilderness. (Link.) The article linked says the salamander wasn't even discovered until the 1960's. It is found only on Shenandoah and North Mountain of western Virginia and eastern West Virginia, and only between 2,400 and 4,300 feet in elevation. The Cow Knob Salamander is listed as a“Species At Risk” by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a “Species of Special Concern” in Virginia and West Virginia and “Near Threatened” on International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Redlist, according to Virginia Wilderness Committee.

- An Ontario, Canada road is closed during parts of the year because of an endangered Salamander (Link).

- In Texas, two legislators have gone so far as to introduce bills to prevent a couple of Lone Star State Salamanders from obtaining endangered species status, in order to keep the amphibian from affecting construction projects in that state. (Link.)

So what is it about Salamanders?

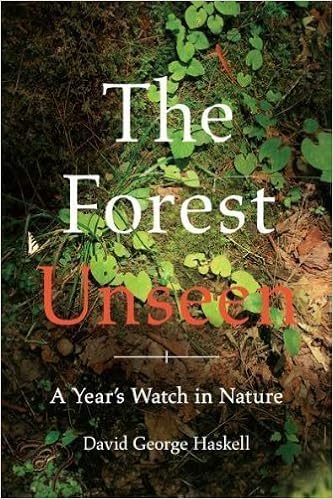

Why does it always seem to be the salamander that is endangered? It is a question I had wondered, but never pursued, until I came across the answer in a wonderful book I am reading. I purchased The Forest Unseen because of the incredible reviews the book receives on Amazon. It is about the author's observations of a small square of old growth forest land on a slope in southeastern Tennessee. The author returned to this spot many times over the year he wrote the book, and documented what he saw in wonderful prose. Each chapter is seldom more than 5 pages long - perfect for reading before turning out the light for the night.

The book is one that I have been slowly working my way through, as I savor each new topic author Haskell gives to me. Reading it in one sitting would not do it justice, though it is not a large book. The chapter entitled "February 28th - Salamander" gave me the "ah ha!" moment about salamanders. Haskell writes that adult salamanders "rarely stray more than a few meters; some individuals move farther downward into the soil than they do across the surface..." - as much as 7 meters below ground during winter. "Because they seldom move far, the salamanders on different sides of a mountain or valley are unlikely to interbreed." Over the eons, they evolve differently while adapting to the unique conditions of their particular environment. "The Appalachian Mountains are ancient rocks and...[parts] have never been covered by a killing sheet of ice-age glaciers. The salamanders here have therefore had time to explode in a burst of diversity that is unmatched anywhere on the planet." Many salamanders have evolved to the point that they don't even have lungs. "Evolution has discarded Plethodon's lungs to make its mouth a more effective snare. By eliminating the windpipe and breathing through its skin, the salamander frees its maw to wrestle prey without pause for breath."

Salamanders therefore require moisture to keep its skin wet and breathe, following "cool, humid air like nomads, moving in and out of the soil as humidity changes." In summer, salamanders are usually found at night. Building a road or clear cutting a forest dries up parts of their territory, killing all salamanders there and separating salamanders from the rest of their territory. And salamanders, because they do not stray far, are very slow to repopulate a disturbed area. A 1988 study of the Cow Knob and Red-backed Salamanders (the latter a much more common species) on Shenandoah Mountain found no salamanders at one of their collection sites - where there had been a clear cut - attributing the animal's absence to the fact that "the lack of canopy cover prevented moisture retention." Link.

So, it appears that Salamanders do not roam, which means that over the eons many different varieties have evolved among the ancient rocks of the Appalachians. And, because they require moisture to survive, they are very susceptible to changes in their immediate area, such as through logging or construction. (Ultimately, also, through climate change.) That is why it always seems to be a salamander that is the endangered animal.

There are many different species of salamander in the Virginia mountains. The Department of Game and Inland Fisheries currently lists 48 species in the state (Link), and new species are not unheard of. Seventeen are from the family Plethodontidae, which are the lungless salamanders - out of 55 species currently known worldwide. (Other types of Virginia Salamanders include those known as "red salamanders" or "mud salamanders," those known as "dusky salamanders," - which are also lungless, and I don't know what is different between the two lungless types, those known as "mole salamanders," and those known as "brook salamanders," "cave salamanders," or "blind salamanders.")

The most common salamander is the Red-backed Salamander (mentioned above). William Needham (who writes on natural history topics for the PATC Newsletter and maintains a wonderfully informative website - Link), reports that Red-backed Salamanders make up "about 94 per cent of the total salamander biomass. The reason for this is that they have evolved to tolerate the cold better than other salamanders." Link.

Several of the Virginia lungless salamanders have "among the smallest ranges of any mainland vertebrates in North America." (Link.) These include:

- Big Levels Salamander (Plethodon sherando), named after, and inhabiting, the region between Sherando Lake and the summit of Bald Mountain at the end of the Torry Ridge Trail known as Big Levels. It was first named only in 2004, well after I started hiking in this area. They live above 2000 feet elevation (just higher than Sherando Lake) and are classified as "Vulnerable" because their range is so small. Link.

|

| Plethodon sherando; Big Levels Salamander ©2015 Will Lattea |

- Peaks of Otter Salamander (Plethodon hubrichti), found in forest habitats above 2775 feet within a narrow 19 km long stretch of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia near the Peaks of Otter (Petranka 1998). Classified as "Vulnerable," also due to a small range. Link.

|

| Peaks of Otter Salamander (Link) |

- Shenandoah Salamander (Plethodon shenandoah), which is listed as federally endangered, is found in talus outcrops on three mountains in Shendandoah National Park - Hawksbill, Stony Man, and The Pinnacles. It is only found at elevations at elevations above 3000 feet and is confined to deep pockets of soil within the talus on the north and northwestern faces of these mountains in mixed-conifer forest. The higher level of critical status is a result of this species' extremely limited range, and also due to greater competition than other salamanders listed with the more common Red-backed Salamander for territory.

|

| Shenandoah Salamander (from Wikipedia) |

So how cool is that? Some of my favorite hiking areas near Central Virginia not only have great trails, but they are home to very rare and exclusive residents. I have reason to go back to these areas in 2016, to see if I can witness some of these rare creatures.